In contemporary society, the idealisation of thinness and the denigration of fatness have become dominant cultural ideals and are now the reference model to which men and women aspire when caring for their bodies. This “cult of thinness” is intensified by social media, which promotes a homogenised body standard that is unattainable for the majority of people.

However, in the early twentieth century, being overweight functioned as a prestige marker, symbolising social privilege and wealth. This could cause problems for middle-class people who were naturally thin, since they risked being mistaken for poor and malnourished. And at a time of great class conflict and social divisions, being confused for an emaciated working-class person was a fate worse than death for some.

These fears became so pervasive that middle-class men and women began to seek ways to look heavier by padding their clothes or wearing baggier attire, but this only provided a temporary fix.

Enter Sargol!

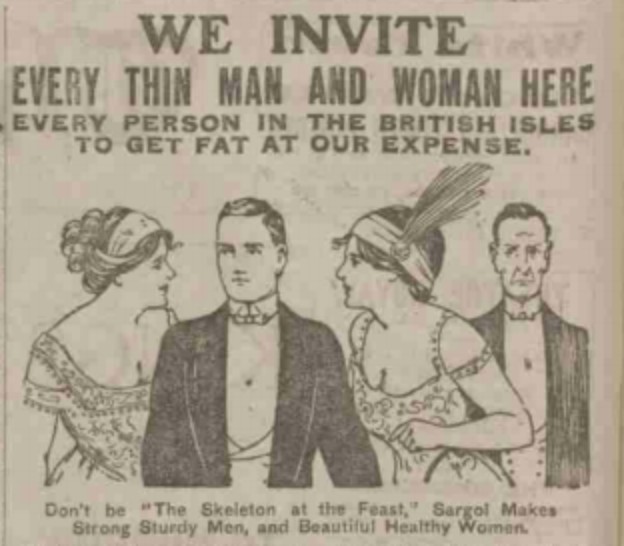

Source: Leeds Mercury, 22 January 1913 (Figure 1)

Launched onto the market in 1912, Sargol was a ‘miracle’ drug that was guaranteed to make consumers “plump, popular and attractive.” Its advertisements were published widely in middle-class newspapers and journals with the aim of promoting fatness as a healthy lifestyle choice, but more importantly, as a way of distinguishing oneself from the “scraggy” working classes. Each advertisement came with a free coupon, encouraging customers to “get fat at our expense.”

Headings advised readers that Sargol would counter “the humiliation and embarrassment of being skinny” and stop them from being “the skeleton at the feast.” Accompanying drawings clearly framed the fat-thin dichotomy as a class struggle, with ‘before and after’ images of middle-class men in bowler hats and tuxedos and women in smart dresses, fascinators and bouffant hairstyles.

Source: John Bull, 22 June 1912 (Figure 2)

In the ‘before’ images, the figures have their heads bowed, with frowns on their faces and hands in their pockets, while in the ‘after’ images, their heads are raised, faces are smiling and biceps are flexed. The advertisements, therefore, become stories about change, evoking the idea that the person on the left can become the person on the right – their future self – if they start taking Sargol immediately.

The language of the advertisements is also clearly class-based, warning women that “no matter how expensively dressed” they are, their “boniness” means that their clothes “will never look good,” while skinny men will always “fail to gain social or business recognition” on account of their “starved appearance.”

Furthermore, readers are told that “scraggy men never look like real money” and that they will be “crowded aside in the race for success.” Even worse, they will be “subject to sneers and rebuffs,” as well as “mortification” when they inevitably “lose popularity.” Skinny women are also frequently portrayed as “withered-up old shrimps with hips like two oyster shells nailed to a board,” shrimps and oysters being cheap foods that had a strong association with the working classes at this time.

One particular advertisement ‘skinny shames’ in its depiction of a plump middle-class couple sunbathing on a beach pointing and looking back in disgust at an emaciated working-class couple. The caption reads “Look at that pair of skinny scarecrows! Why don’t they try Sargol?” The implication is clear: taking Sargol gives you status, recognition and respect, while not taking it reduces you to the status of a poor and unrespectable “scrag” or “lath”.

Source: Sheffield Weekly Telegraph, 25 January 1913 (Figure 3)

Sargol built credibility by formulating its advertisements in such a way that they tapped into growing public interest in science and the belief that anything novel or innovative would improve one’s life. Capitalising on the popularity of Darwinism, the brand described itself as the “missing link” between food eating and fat making necessary to “win in the battle of life.”

According to the advertisements, Sargol is a “new tissue builder and flesh former” that contains “the active principle of assimilation,” which is essential for proper absorption of food. Moreover, it is guaranteed to “increase cell growth, make indigestion and other stomach troubles disappear as if by magic and make an old dyspeptic or a sufferer from weak nerves or lack of vitality feel like a 2-year-old.”

Advertisements also advise consumers on how to take Sargol: three times a day with every meal. They boldly claim that after just five minutes, its effects start to take place and users will gain weight at one pound per day. No medical or scientific evidence is provided to support these points; we are just supposed to take them at face value. Equally, we are told that Sargol is consumed by over one million people yearly, but there is no way of testing this claim. Testimonials from satisfied consumers also appear in advertisements, but only their initials or first names are left, making it hard to trace whether they actually existed.

Shortly after Sargol’s release, an article appeared in the British Medical Journal, with a breakdown of its ingredients: saw palmetto, calcium, sodium, potassium, nux vomica, sugar and albumen. In other words, chemical analysis had demonstrated that the drug was a placebo that offered no real medical benefits or weight gain.

In the USA, Sargol also contained lecithin, but this was deliberately removed in UK products as the brand would have been marked as a poison under the Pharmacy Act 1868. Without lecithin, Sargol did not need to list its ingredients on its packaging, which gave the product a greater air of mystery as a wonder cure for skinniness.

From 1912 to 1916, Sargol made around £3,000,000 in profit. However, things began to turn sour in 1917 after the company was taken to court in the USA for quackery. After a three-month trial, it was shut down and fined over $30,000. However, its UK subsidiary was not affected and continued to trade for almost twenty more years.

By the time the company had folded in 1937, their marketing strategy had markedly transformed. Now, Sargol focused on guarding against nervous breakdown, which had become a “prestige disease” associated with busy working lives. There was no scientific evidence to support this and there was nothing to distinguish this ‘new’ Sargol from the Sargol that had been marketed as helping consumers gain weight. Nonetheless, in promptly rebranding itself, Sargol was able to retain its middle-class audience, as well as its market share.

This transformation in marketing strategy was prompted by changing attitudes towards fatness throughout the 1920s and 1930s. While this was partially influenced by increasing medical knowledge about the dangers of obesity, the biggest factor by far was the boom in movies and photography, which had made people far more body conscious.

Suddenly, plumpness was seen as an “aesthetic threat and health risk” tied to the growing notion of bodies as consumable objects on display and medical problems that would place burdens on healthcare systems. Bodies were now something that had to be regularly managed through healthy diet, exercise regimes and willpower. Furthermore, obesity became increasingly associated with the working classes, tied up with perceptions of laziness and personal inadequacy. These ideas have remained constant in our society ever since.

Although Sargol was nothing but a ‘get fat quick’ scam, it highlights how marketers were able to create an artificial demand for the product amongst middle-class consumers anxious to distinguish themselves from the working classes. It, therefore, stands as a key example of the inherent dangers of tying up products with class relations, showcasing body weight as another way of distinguishing the powerful from the powerless.

This study was conducted in collaboration with the FoodKom research group at Örebro University, led by Prof. Göran Eriksson, as part of the “Communication of ‘Good’ Foods and Healthy Lifestyles” project.

Interesting to find these ads simultaneously published with “get slim” ads promising “no one need remain fat now” … it seems quack cures were being targeted at all sorts of body types!. The flapper style favored the thin and small chested look for women so these “get plump” ads probably gradually decreased from this point on out. Would be interesting to study that!

LikeLiked by 1 person